UVM News and Readings: January 2025

News & Events

Coming This February: New Social Hour Schedule after Basilica TLM

As we announced last month, at its November meeting the UVM board looked at how we might enhance our lineup of social hours after both Sunday and First Saturday masses. While we are still looking for volunteers from the TLM community to form a social hour committee that would more actively manage the logistics of the social hours to ensure there is enough food, coffee, condiments, etc., beginning in February, there will be two social hours per month at the Basilica in Lewiston. Rather than the 3rd Sunday, there will be social hours on the 2nd and 4th Sunday of each month. Basilica social hours in February will be on the 9th and 23rd. For January, however, there will still be one social hour on the third Sunday.

If you are interested in helping support our TLM community on the social hour committee, please email UVM at info@unavocemaine.org.

Psalterium Institute Presents Epiphany Lessons & Carols

On Friday and Saturday, January 3rd and 4th, the Psalterium Institute, which we introduced in the November newsletter, will be performing an evening of choral music for the Christmas season, including music by Victoria, Bouzignac, Sweelinck, Host and a special presentation by the Institute Children’s Choirs and harpist Patrice Lockhart of Benjamin Britten’s “A Ceremony of Carols.” Schedule of performances is:

Friday, January 3 at 6:30 PM Saint John the Baptist Church, Brunswick

Saturday, January 4 at 6:30 PM Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Portland

The Heart Has its Reasons

by Gavin Ashenden

Latin functions as a language of love, of adoration, of mystery and of longing.

Dr. Dick and I sit at the back of Mass together. We are both tenors. I would not want to say ‘elderly’; I would prefer to say that we share a degree of intellectual and musical experience. But basically, we are both two retired ex-academics past the first bloom of youth. A long way past.

We have many things in common – the same size, the same vocal range, a trifle given to pedantry, but Dick is a scientist and I am not. Both of us are converts to the faith. We fell to discussing the Latin Mass. The conversation grew quite energized. Dick is a Novus Ordo kind of a guy through and through.

He was a senior lecturer in biology. He likes his facts and he likes clarity. When I suggested that the restriction of the Latin Mass was an impoverishment, he expostulated with vigorous denial.

“Of course it isn’t,” he said. “No one needs the Latin Mass. No one understands it. The liturgy has to be in the vernacular. It must be comprehensible, or else the laity are excluded.”

There was a time when I would have agreed with Dick. I remember as a recent convert to Christianity when I was a student, I had become very impatient with the ornate language of Cranmer in the 1662 prayer book. After years of attending liturgy without encountering the living God, I too was inclined to favor the contemporary, the accessible, the familiar. Beauty, cadence and elegance were all very well, but perhaps, went the familiar puritan argument, they could sometimes be a means of idolatry – ends in themselves, more than vehicles of supernatural encounter.

I tried the argument of Pope St John XXIII (in Veterum Sapienta) that perhaps if Latin was not objectively a source of holiness it might passively be so, having been sanctified by constant use in prayer? That didn’t pass the functionality test either, however.

Nor does Dick have much history. Not many biologists do. I told him how deeply I was moved by knowing I was using almost identical words and structures to my great heroes of Catholic history, prayer and thought.

In fact, I wanted to go further and say that through my whole life as a Protestant I carried the pain of not being in communion with disciples I loved – St Martin de Tours, St Anselm and St Augustine. And as for the home-growns, Bede, Alfred, Becket, Julian of Norwich, More, Fisher – the list is endless.

As with many sacramentally nostalgic ex-Anglican ministers, I was taught how to say the Latin Mass, in (sacramentally ineffective) imitation of the Catholic Church, and I immediately got the point. It was all about holiness and miracle.

What one touched, how one touched, where one moved at the altar, how one moved, what one wore, how one wore it and how one prayed when dressing, were all about holiness and the miraculous.

The choreography of priests and servers, given as much attention as any ballet or drama on stage, because something more important than a ballet or a drama is taking place, gives an indication that something of supreme beauty and importance is going on here.

There are many reasons why our generation of Catholics have found difficulty in believing in the miracle of the Mass. The alarming figure in the USA is the now well-known 69 percent surveyed who disbelieve the essential supernatural miracle and only 31 percent who do.

So, I want to ask Dick, how the culture of intelligibility is going for the Church? What has rational, accessible, colloquial, vernacular communication achieved? Is openness to the experience of the supernatural, is vulnerability to the miraculous achieved by the rational calculations of the mind; or is it perceived by the intuitions and longings of the heart?

Perhaps there is an advantage in using words from a second rather than a first language. The first language in which everyone is fluent may be the language of contract, bargains, measurement, argument, acquisition, negotiation; but perhaps Latin can offer itself as a second language; in which it functions as a language of love, of adoration, of mystery and of longing. It offers itself as the language not of the mind but of the heart.

It may not please Dick the scientist at first sight. But Dick may have forgotten that his laboratory of the mind in which empirical science is tested and discovered and in which biological life is tested and defined, is a different venture from the liturgy. The liturgy may instead act as a laboratory for the heart in which the supernatural is perceived and the life of the soul is rescued, mended and restored. The promise of God through the prophets was always, “I will give you a new heart” (Jeremiah 31).

It was a mathematician, Blaise Pascal, who got to the heart of the matter so succinctly when he wrote: “The heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of... We know the truth not only by the reason, but by the heart.”

And liturgical Latin is pre-eminently the language of the heart.

Reproduced from Mass of Ages, the magazine of the Latin Mass Society of England and Wales.

The Liturgical Year

Very Rev. Dom Prosper Guéranger Abbot of Solesmes, 1833-1875

January 6 - Epiphany of Our Lord

The Feast of the Epiphany is the continuation of the mystery of Christmas; but it appears on the Calendar of the Church with its own special character. Its very name, which signifies Manifestation, implies that it celebrates the apparition of God to his creatures.

For several centuries, the Nativity of our Lord was kept on this day; and when in the year 376 the decree of the Holy See obliged all Churches to keep the Nativity on the 25th of December, as Rome did—the Sixth of January was not robbed of all its ancient glory. It was still to be called the Epiphany, and the Baptism of our Lord Jesus Christ was also commemorated on this same Feast, which Tradition had marked as the day on which that Baptism took place.

The Greek Church gives this Feast the venerable and mysterious name of Theophania, which is of such frequent recurrence in the early Fathers as signifying a divine Apparition. We find this name applied to this Feast by Eusebius, St. Gregory Nazianzum, and St. Isidore of Pelusium. In the liturgical books of the Melchite Church the Feast goes under no other name.

The Orientals call this solemnity also the holy Lights, on account of its being the day on which Baptism was administered (for, as we have just mentioned, our Lord was baptized on this same day). Baptism is called by the holy Fathers Illumination, and they who received it Illuminated.

Lastly, this Feast is called, in many countries, King’s Feast: it is, of course, an allusion to the Magi, whose journey to Bethlehem is so continually mentioned in today’s Office.

The Epiphany shares with the Feasts of Christmas, Easter, Ascension, and Pentecost the honor of being called, in the Canon of the Mass, a Day most holy. It is also one of the cardinal Feasts, that is, one of those on which the arrangement of the Christian Year is based; for as we have Sundays after Easter and Sundays after Pentecost, so also we count six Sundays after the Epiphany.

The Epiphany is indeed a great Feast, and the joy caused us by the Birth of our Jesus must be renewed on it, for, as though it were a second Christmas Day, it shows us our Incarnate God in a new light. It leaves us all the sweetness of the dear Babe of Bethlehem, who hath appeared to us already in love; but to this it adds its own grand manifestation of the divinity of our Jesus. At Christmas, it was a few Shepherds that were invited by the Angels to go and recognize the Word made Flesh; but now, at the Epiphany, the voice of God himself calls the whole world to adore this Jesus, and hear him.

The mystery of the Epiphany brings upon us three magnificent rays of the Sun of Justice, our Savior. In the calendar of pagan Rome, this sixth day of January was devoted to the celebration of a triple triumph of Augustus, the founder of the Roman Empire: but when Jesus, our Prince of peace, whose empire knows no limits, had secured victory to his Church by the blood of the Martyrs—then did this his Church decree that a triple triumph of the Immortal King should be substituted, in the Christian Calendar, for those other three triumphs which had been won by the adopted son of Cæsar.

The Sixth of January, therefore, restored the celebration of our Lord’s Birth to the Twenty-Fifth of December; but in return, there were united in the one same Epiphany three manifestations of Jesus’ glory: the mystery of the Magi coming from the East under the guidance of a star, and adoring the Infant of Bethlehem as the divine King; the mystery of the Baptism of Christ, who, while standing in the waters of the Jordan, was proclaimed by the Eternal Father as Son of God; and thirdly, the mystery of the divine power of this same Jesus, when he changed the water into wine at the marriage feast of Cana.

January 14 – Saint Hilary, Bishop, Confessor, and Doctor of the Church

After having consecrated the joyous Octave of the Epiphany to the glory of the Emmanuel who was manifested to the earth, the Church—incessantly occupied with the Divine Child and his august Mother during the whole time from Christmas Day to that whereon Mary will bring Jesus to the Temple, there to be offered to God as the law prescribes—the Church, we say, has on her Calendar of this portion of the year the names of many glorious Saints who shine like so many stars on the path which leads us from the joys of the Nativity of our Lord to the sacred mystery of our Lady’s Purification.

And firstly, there comes before us, on the very morrow of the day consecrated to the Baptism of Jesus, the faithful and courageous Hilary—the pride of the Churches of Gaul and the worthy associate of Athanasius and Eusebius of Vercelli in the battle fought for the Divinity of our Emmanuel. Scarcely were the cruel persecution of paganism over when there commenced the fierce contest with Arianism, which had sworn to deprive of the glory and honors of his divinity that Jesus, who had conquered, by his Martyrs, over the violence and craft of the Roman Emperors. The Church had won her liberty by shedding her blood, and it was not likely that she would be less courageous on the new battlefield into which she was driven. Many were the Martyrs that were put to death by her new enemies—Christian, though heretical, Princes: it was for the Divinity of our Lord, who had mercifully appeared on the earth in the weakness of human flesh, that they shed their blood. Side by side with these, there stood those holy and illustrious Doctors who, with the martyr-spirit within them, defended, by their learning and eloquence, the Nicene Faith, which was the Faith of the Apostles. In the foremost rank of these latter we behold the Saint of today, covered with the rich laurels of his brave confessorship, Hilary, who, as St. Jerome says of him, was brought up in the pompous school of Gaul, yet had called the flowers of Grecian science, and became the Rhone of Latin eloquence. St. Augustine calls him the illustrious Doctor of the Churches.

Though gifted with the most extraordinary talents, and one of the most learned men of the age, yet St. Hilary’s greatest glory is his intense love for the Incarnate Word, and his zeal for the Liberty of the Church. His great soul thirsted after martyrdom and, by the unflinching love of truth which such a spirit gave him, he was the brave champion of the Church in that trying period when Faith, that had stood the brunt of persecution, seemed to be on the point of being betrayed by the craft of Princes and the cowardice of temporizing and unorthodox Pastors.

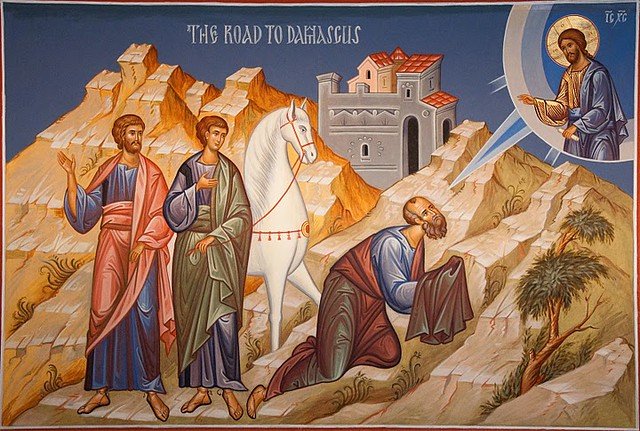

January 25 – The Conversion of Saint Paul

We have already seen how the Gentiles, in the person of the Three Magi, offered their mystic gifts to the Divine Child of Bethlehem, and received from him, in return, the precious gifts of faith, hope, and charity. The harvest is ripe; it is time for the reaper to come. But, who is to be God’s labourer? The Apostles of Christ are still living under the very shadow of mount Sion. All of them have received the mission to preach the gospel of salvation to the uttermost parts of the world; but not one among them has, as yet, received the special character of Apostle of the Gentiles. Peter, who had received the Apostleship of Circumcision, (Galatians 2:8) is sent specially, as was Christ himself, to the sheep that are lost of the house of Israel, (Matthew 15:24) And yet, as he is the Head and the Foundation, it belongs to him to open the door of Faith to the Gentiles; (Acts 14:26) which he solemnly does, by conferring Baptism on Cornelius, the Roman Centurion.

But the Church is to have one more Apostle - an Apostle for the Gentiles - and he is to be the fruit of the martyrdom and prayer of St. Stephen. Saul, a citizen of Tarsus, has not seen Christ in the flesh, and yet Christ alone can make an Apostle. It is, then, from heaven, where he reigns impassible and glorified, that Jesus will call Saul to be his disciple, just as, during the period of his active life, he called the fishermen of Genesareth to follow him and hearken to his teachings. The Son of God will raise Saul up to the third heaven, and there will reveal to him all his mysteries: and when Saul, having come down again to this earth, shall have seen Peter, (Galatians 1:18) and compared his Gospel with that recognised by Peter (Galatians 2:2) - he can say, in all truth, that he is an Apostle of Christ Jesus, (Galatians 1:1) and frequently elsewhere) and that he has done nothing less than the great Apostles. (2 Corinthians 11:5)

It is on this glorious day of the Conversion of Saul, who is soon to change his name into Paul, that this great work is commenced. It is on this day, that is heard the Almighty voice which breaketh the cedars of Libanus, (Psalm 28:5) and can make a persecuting Jew become first a Christian, and then an Apostle. This admirable transformation had been prophesied by Jacob, when, upon his death-bed, he unfolded, to each of his sons, the future of the tribe of which he was to be the father. Juda was to have the precedence of honour; from his royal race, was to be born the Redeemer, the Expected of nations. Benjamin’s turn came; his glory is not to be compared with that of his brother Juda, and yet it was to be very great - for, from his tribe, is to be born Paul, the Apostle of the Gentile nations.